Craig Willse and Dean Spade have been collaborating for 20 years on projects related to queer and trans anti-poverty, anti-prison, and anti-war politics. Craig is Associate Professor of Cultural Studies at George Mason University, and is recently the author of The Value of Homelessness: Managing Surplus Life in the United States. Dean is Associate Professor at Seattle University School of Law, and is the author of Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics and the Limits of the Law.

Craig: The concept of prison abolition has traveled widely in the past decade, but many are still encountering it for the first time. For someone new to abolition politics, what are its key tenets and insights?

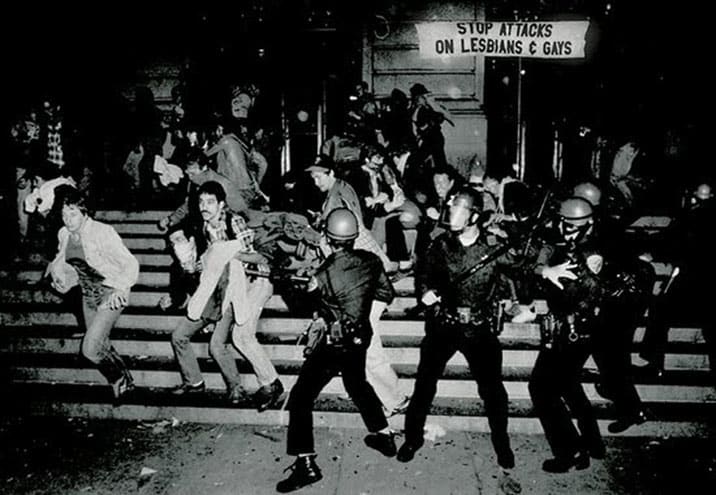

Dean: First, abolition is about recognizing the fundamental nature of policing and imprisonment. Historians tell us that policing in the United States has been a project of colonial racial and economic control and stifling dissent since it began. Some of the police forces in the US South have their origin in slave patrols, and are thus, at their very conception, anti-Black. During the 1960’s and 1970’s anti-racist movement organizations, like the Black Panther Party and the Young Lords, described the police as an occupying force in Black and brown communities and armed themselves in self-defense against the police.

Movement leaders like Fred Hampton, Leonard Peltier and Assata Shakur were imprisoned or assassinated when the FBI and local police set out to dismantle emerging movements. From the 1980’s onward, policing and imprisonment drastically expanded in the US. Some of the engines of this expansion have been the War on Drugs, sentencing reforms like three strikes bills, and “broken windows” policing in cities that criminalizes poor people, indigenous and people of color for sleeping outside, loitering, and panhandling. Empowering law enforcement and unleashing them onto marginalized communities was a bipartisan U.S. project. In all forms of policing and imprisonment, people of color, people with disabilities, indigenous people, immigrants and LGBT people are targeted.

Abolitionists have identified how, throughout the history of imprisonment, efforts at reform have actually expanded policing and prisons . Concerns about women being in prison with men led to the creation of women’s prisons, which then spread until they existed everywhere. Similarly, the creation of prisons for children was supposed to make imprisoning children more humane, but actually just increased the imprisonment of children. Expansion frequently occurs on the basis of improving policing or imprisonment, so abolitionists are wary of calls to create a safer, kinder, softer, or more just way of policing or caging people. Instead, our long-term goal is to end imprisonment and policing, and we assess whether particular reforms are a step toward that (because they decriminalize things, or get people out, or reduce the number of cops or cages) or are a step that entrenches policing while masquerading as a justice-oriented reform. We oppose reforms that further legitimize the police and expand their equipment or power. These might be reforms to hire new or more cops from marginalized communities, or to give cops more technology that will supposedly make them more accurate or just, or to give cops new roles so that they act as social workers in some way in the community. It also means we oppose prison reforms that expand prisons, justified by concerns about overcrowding or the need to build specialized facilities for vulnerable people. We do not believe that a safe or humane cage for a human can be built. We want people get out of prison. We do not believe that policing can be fixed to become fair and provide safety. Policing is working exactly as it was designed to work, as it has always worked: to target and criminalize marginalized people and protect the interests of the rich. We want to build a world without police or prisons where safety comes through solidarity, mutual aid, and interdependence.

Craig: When in your own work did you first encounter abolition politics? How did it transform your approach to activism and organizing?

Dean: I first remember hearing about abolition while I was a law student at UCLA, at the 1998 conference in Berkeley put on by Critical Resistance (CR). I continued to connect with abolitionists after that, through CR, the Prison Moratorium Project in New York, and feminist and queer organizations. Abolition transformed my politics at a very deep level. It gave me a way of understanding, not only in the realm of criminal punishment but more broadly, the problems with reforming harmful systems that we really want to be dismantling. This is a big deal since I came of age during the emergence of a new neoliberal gay politics that was all about seeking reforms to include gays and lesbians (and later trans people) in institutions that left social movements had long identified as brutal systems of maldistribution, control and violence: the military, marriage, policing and criminal punishment. Abolition politics helped me understand how LGBT recognition and inclusion were operating to rehabilitate these institutions and brand them as sites of liberation rather than social control and violence.

Abolition also helped me understand the importance for activists to discern the difference between reform efforts that claim to benefit some hated community but really build up harmful institutions and reform efforts that dismantle harmful institutions and build the world we want. This distinction is central to my thinking and practice. Abolition also pushes us to envision the world we actually want and to imagine much more creatively than we can when we assume we are stuck with the institutions we have now. Since no society has ever existed with as much imprisonment as the US has now, and since most of human history had nothing like the prisons, professional police forces, militarized borders, and identity documents, we have now, it is entirely possible to imagine otherwise. We are told that police, prison, and border abolition is impossible or unimaginable, but the systems we currently have are very new and unsustainable, so it is essential that we build our immediate and long-term political frameworks around imagining what we actually want and experiment with and debate about what will actually get us there.

Craig: You, along with other JVP members and Palestinian activists in Seattle, have done a lot of work combating what we call “pinkwashing.” Can you explain pinkwashing and where it’s come up in Seattle?

Dean: Activists use “pinkwashing” to describe when institutions, or even individual public figures, try to get good PR by portraying themselves as “gay-friendly.” The term emerged from Palestinian queer and trans activists identifying how Israel was marketing itself, as part of its broader “Brand Israel” campaign, as a “gay friendly” country and a gay tourism destination. This campaign also portrays Palestinians, and more broadly the Arab and Muslim countries surrounding Israel, as homophobic to justify anti-Arab and anti-Muslim racism and Israeli colonialism. Israel engages in this PR work by funding films that depict Israel as a gay haven for queer Palestinians and supporting those films touring in Europe and North America, by touring a trans Israeli Defense Force (IDF) officer around the US to show how accepting the IDF is, and by funding tours of LGBT Israeli activists who talk about gay rights in Israel while never challenging Israeli apartheid and colonialism. Pinkwashing is not just used by Israel. We can see it in the New York Police Department’s rolling out of rainbow striped police cars to market the NYPD as “gay-friendly.” We can see it in the Seattle Police Department’s “Safe Space” campaign, in which they distribute stickers with a rainbow police badge and ask businesses to put them in their front windows. The idea is that if a business has the sticker, you can run in there if facing an anti-LGBT attack and they will call the cops for you. But what do you do if the biggest perpetrator of anti-LGBT violence is the cops? Corporations, government agencies, militaries, and individual politicians use pinkwashing tactics to appear progressive and cover up their actually harmful activities.

Israeli pinkwashing has come up in Seattle numerous times. In 2012, an Israeli Consulate-funded pinkwashing tour, co-organized by Zionist organizations StandWithUs and A Wider Bridge, came through Seattle and planned an event with the City’s LGBT Commission. Activists exposed it as propaganda and got the event canceled, and then a huge backlash ensued. We made a movie about that story that is free to watch online and is a good “pinkwashing 101” tool. After that, our gay mayor at the time, Ed Murray, keynoted a pinkwashing conference in Tel Aviv put on by the premiere pinkwashing organization in the US, A Wider Bridge. We protested his trip in Seattle by dressing as a giant rainbow and going to City Hall on Nakba day with lots of big signs. In 2017, Murray was given an award for being an Israel advocate by StandWithUs. The ongoing relationship between his administration and pinkwashing and Israel advocacy organizations has been a site of continued protest that has raised a lot of awareness about the Palestinian struggle, Israeli apartheid and pinkwashing in Seattle.

Israeli pinkwashing has come up in Seattle numerous times. In 2012, an Israeli Consulate-funded pinkwashing tour, co-organized by Zionist organizations StandWithUs and A Wider Bridge, came through Seattle and planned an event with the City’s LGBT Commission. Activists exposed it as propaganda and got the event canceled, and then a huge backlash ensued. We made a movie about that story that is free to watch online and is a good “pinkwashing 101” tool. After that, our gay mayor at the time, Ed Murray, keynoted a pinkwashing conference in Tel Aviv put on by the premiere pinkwashing organization in the US, A Wider Bridge. We protested his trip in Seattle by dressing as a giant rainbow and going to City Hall on Nakba day with lots of big signs. In 2017, Murray was given an award for being an Israel advocate by StandWithUs. The ongoing relationship between his administration and pinkwashing and Israel advocacy organizations has been a site of continued protest that has raised a lot of awareness about the Palestinian struggle, Israeli apartheid and pinkwashing in Seattle.

Craig: What does an abolition framework offer anti-pinkwashing work?

Dean: I think that there is very significant overlap and interrelation between anti-pinkwashing work and abolition. Both are rejections of normalization. We refuse to have conversations about Israeli “gay rights” that disregard or take for granted Israeli colonialism and apartheid; similarly, we refuse to talk about making surface reforms to policing and prisons (like hiring LGBT cops or passing symbolic anti-discrimination policies that do not do anything) in ways that presume cops or prisons could be desirably safe, just, inclusive, or “diverse.” Both projects require us to have a deep critique of reforms that promise to resolve our movements’ complaints, but actually stabilize the systems of meaning and control we are trying to dismantle. Both anti-pinkwashing work and abolitionist work require us to build collectively cultivated discernment (through debate and experimentation) about what constitutes meaningful change to material conditions and what is just recuperation for the systems and institutions we are trying to dismantle. This is hard work these days.

Craig: How can centering abolition politics in JVP’s work connect us to other struggles for racial justice, in the US and around the globe?

This is such an important question right now, as JVP builds the Deadly Exchange campaign and launches its study group about Zionism. With both, JVP is building shared analysis among chapters and members about our most fundamental commitments to ending white supremacy and colonialism. A few months ago, I created a webinar for JVP members to support the Deadly Exchange campaign aimed at introducing members to abolition and abolitionist analysis of police reform. My hope was to help members and chapters think about how to build the campaign in ways that are in solidarity with anti-police and anti-prison movements, rather than inadvertently undermining them. I offered participants in the webinar a few suggestions about talking points that we might avoid, and what we might say instead, to avoid common pitfalls. Here is what I suggested:

Avoid Saying: “Police do not need to be trained in Israel to make us safe.”

- Why: Pro-police and pro-criminalization PR claim that police make us safe. Anti-racist movements identify police as an enormous source of violence in communities of color, not a source of safety. If we use talking points that affirm that police make “us” safe, we are working at odds with our allies and possibly mobilizing an idea that perpetuates racist violence.

- What We Can Say Instead:

Police in the US bring devastating violence to communities of color. The Deadly Exchange campaign is trying to fight against one way that police violence is being enhanced by stopping programs that send US police to Israel to be trained by the Israeli military, an expert force in racist and colonial state violence. US cops don’t need more of that and Jewish organizations shouldn’t be supporting it.

Avoid Saying: “US police are a civilian force. They shouldn’t be going to Israel to be trained by a military.”

- Why: Both the US and Israel are settler colonial countries–places where a settler population came in aiming to clear the land of indigenous people and establish settler government, institutions and population.This means that all the police and military of both countries are doing the work of colonial violence. In both Israel and the US, the police and military are forces of racism, xenophobia and anti-indigenous violence. Inside the countries, distinctions are made between things like “civil,” “criminal,” or “military” institutions and systems. US movements against racism have question those distinctions, saying the police are a colonizing force in Black and brown communities, showing how domestic policing is part of targeting indigenous people to eradicate their nations. These movements have argued that the war that the US makes on indigenous people and people of color is done by purportedly civilian institutions, like police, all the time. When we talk like we believe in the government’s distinctions between civilian and military, we ignore the wisdom of the movements of people targeted. Also, it makes it seem like we would be fine with an exchange program between “civilian” forces, but actually that would be horrible too. Whatever the governments of the US and Israel call it, we are opposing anything that enhances the ability to control and kill people for the benefit of white people, rich people, and racist regimes.

- What We Can Say Instead:

We want to stop these exchange programs where the Israeli military trades worst practices with US law enforcement. Both forces are engaged in racist, colonial violence against targeted people in the name of “security”, and we want to take apart that violence and make it stop. Stopping these exchanges is one piece of this work.

Avoid Saying: “Israel denies Palestinians’ rights to a fair trial and other basic rights. We don’t want those practices brought back to the US with these exchanges.”

- Why: Because the US policing, prosecution and court systems are also racist and unfair from start to finish. In every stage of these systems, we can see clear racial targeting. Racism in the US determines who will be stopped, who will be arrested, what they will be charged with, how long they will spend in pre-trial detention, who can afford bail, what race the judge is likely to be, what race the jury is likely to be, who will have to take a plea deal, who will get the longest sentences, who will experience the worst prison conditions, who will serve the longest proportion of a prison sentence, who will be given the most restrictive parole and probation conditions, who will be returned to prison, who will be deported. We want to avoid creating a false idea that law enforcement is racist and colonial but not the US. In both systems, the court system is unfair.

- What We Can Say Instead:

We don’t want US law enforcement getting trained in Israel and bringing back the practices used by the IDF against Palestinians to further expand and enhance the racism of US policing, prosecution and criminalization.

Avoid Saying: “The key problem is the privatization of police and prisons….”

- Why: Progressive media has latched on to the idea of private prisons and policing in recent years, and many of us have begun to use this as a central talking point about what is wrong with prisons and policing. Making profit off imprisonment is reprehensible, and private prisons are sites of extreme violence. However, most prisons in the US are not private, and even if we got rid of private prisons and policing, we would still have a mammoth, racist, violent policing and imprisonment system. Focusing our talking points on the private prison industry misses the larger target which is the whole system of policing and imprisonment.

- Reading resources on this point:

- Peter Wagner, Are Private Prisons Driving Mass Incarceration?

- Ruth Wilson Gilmore, The Worrying State of the Anti-Prison Movement

- Critical Resistance, Private Prisons

- What We Can Say Instead:

If other people bring up private prisons, we can agree they are terrible and that the Deadly Exchanges campaign is aimed at reducing partnerships between Jewish organizations and police departments in which there are many private and public resources being mobilized to increase “worst practices” of racist police and military systems.

All of these points, for me, come from the fundamental abolitionist insight that we are working to dismantle policing and prisons. Along the way, we must fight to prevent our work from being made into system-fortifying and system-expanding work. Just as critiques of Israel are now folded into Zionist frameworks, policing and prison reform work is used as a basis for legitimizing and expanding punishment structures. Abolitionist and anti-colonial commitments support us to make our work more effective while avoiding the traps of cooptation and misdirection that can undermine our efforts.