By Lee Sharkey

I was one of the ones who crossed over.

They told me I was a chosen one.

I crossed into the city. What was I carrying on my shoulders?

The parts of the sentence were separated, I saw, by centuries.

I crossed carrying a sentence on my shoulders.

The city gates read City of Refuge.

They showed me a city with water for cleaning and drinking.

There was bread in the city to quiet hunger.

If you come without intention, they said, the city will open.

They said, here the avenger cannot enter.

I asked, but how have I come to this city.

They said, better to ask, where are the city’s famed bookstalls.

Many a head has bent over a book and asked many a question.

Who am I to come to this city, I asked, and bowed my head.

Bread on the water, bread on the water, I asked.

Artist statement

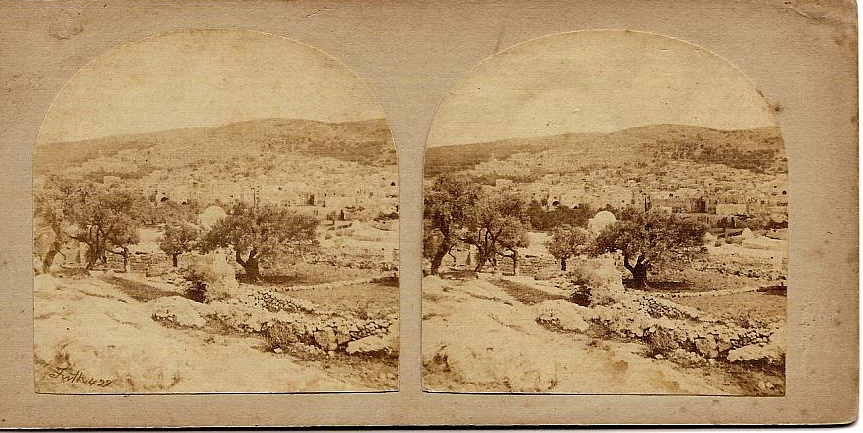

In the Biblical-era kingdoms of Israel and Judah six cities were designated “cities of refuge,” to which those who had committed manslaughter might come and claim the right of asylum. Hebron, whose name derives from the Semitic root for friend, was one such city. The first time I visited Israel/Palestine, in 1979, an Israeli taxi driver drove me and my mother slowly through its narrow streets—an act of provocation, he boasted, against the Palestinians who lived there. Today, Hebron bristles with tension as fewer than a thousand Jewish settlers live barricaded and guarded by the Israeli Defense Forces among 215,000 Palestinians. Demolitions of nearby Palestinian villages proceed unchecked. But for many centuries Hebron was a cultural crossroads with a tradition of hospitality.

It seems crucially important to me, at this time when hatreds divide us and violence upends whole countries’ civilian populations, that we retain the ideal of the City of Refuge, a place of peace and mutual respect where human needs are met and all are welcome who wish to begin anew. The traveler who recounts the tale of his arrival in “The City” has been taught that he/she is one of the “chosen people,” but who exactly constitutes this chosen tribe? What responsibilities does chosenness entail? The speaker of the poem is advised to enter the city “without forethought,” open to experiencing the questions that fill him/her as a casting of bread on the water—the traditional Tashlich ritual for disburdening oneself of the past year’s failings—a first step toward making something better of what lies ahead.

–Lee Sharkey, JVP Artist Council

READ MORE

Imagining Abolition with Haredim

By Ben Ratskoff Because Haredi communities have historically detached their work in Jewish law from the carceral Israeli state, their perspectives on incarceration seem worth exploring in order to imagine alternative political visions of...

Abolishing Prisons and Ending Racism

How to think and what to do about race in order to abolish prisons By Anonymous In 2010, I had a 4-month long psychotic episode during which time I broke several laws, including public disturbance, shoplifting, stalking and whatever it is...

Imagining the World to Come: Call for Submissions

How do we achieve real safety?